With this kick-off to my blog, I want to tell you how I came to this topic of “ecomodernism”.

I was 17 years old when, on April 26, 1986, the event happened that dealt a blow to nuclear energy worldwide from which it would never recover to this day: Chernobyl. From then on, the Greens, who had just been elected to the German Bundestag three years earlier, felt confirmed in the position they had held since their founding: The world must finally get out of “the nuclear”.

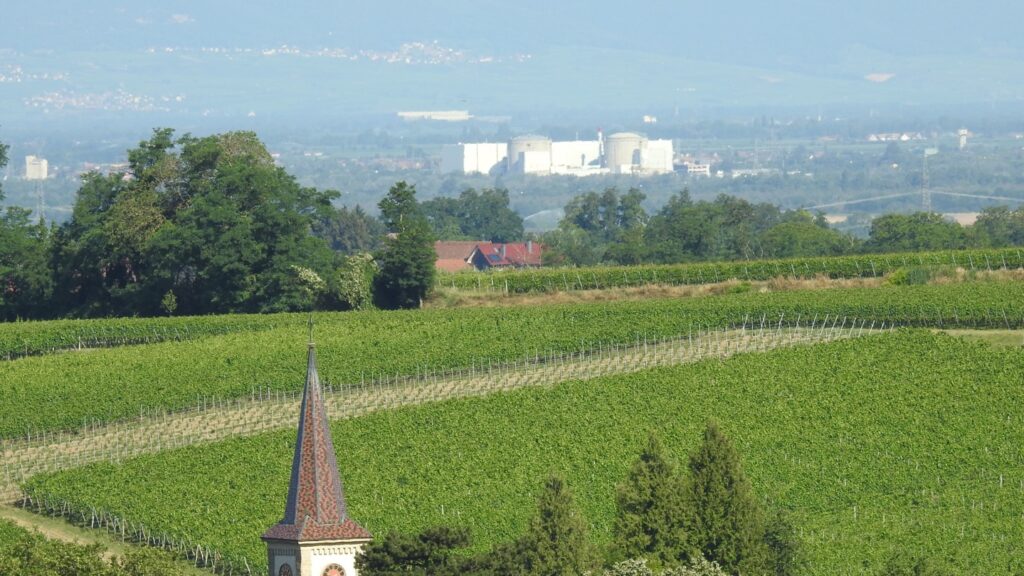

I grew up here in the Markgräflerland, south of Freiburg, as the son of a master vintner, 11 km from the Fessenheim nuclear power plant and 38 km from the Wyhl nuclear power plant, which was still being planned and fought against at the time. I remember very well when the news came about the small transistor radio that we carried with us in the vines while “tying up”. We had showery weather, it was raining lightly.

South Baden is one of the strongholds of the anti-nuclear movement. The “energy rebels” of the EWS Schönau have their headquarters beyond our local mountain Blauen. This is how I was socialized as an opponent of nuclear power: everyone of us here saw Fessenheim as a danger. In 2000, it was clear: the nuclear phase-out, the energy turnaround and the Renewable Energy Sources Act (EEG) must be established politically and legally. The goal of converting the energy industry to 100% renewables was set.

Enthusiasm for electric mobility – triggered by the Tesla Roadster

I first became interested in the subject again in 2008, in the middle of my professional life as a business information scientist – rather by chance, because at that time my wife was doing an internship at a PR agency that advised companies in the renewable energy sector. In 2008, Tesla (then still Tesla Motors) also introduced its Roadster, and from then on, electric mobility in particular was my first topic in this direction – and it still is.

Fukushima and energy turnaround – foundation of Bürgerenergie Südbaden eG

The second nuclear accident in Fukushima in March 2011 fell on the fertile ground of my previous attitude. From then on it was clear to me: 100% renewable energies (RE) were needed. From then on, I dealt extensively with the topic of RE, also in connection with electric mobility. In 2012, the then managing director of the Müllheim-Staufen public utilities approached me about becoming a co-founder of an energy cooperative (BEGS) and a member of the supervisory board. Since then, I have been a founding member and have even given small talks here and there about the energy transition and electric mobility.

In 2011, I switched to an Opel Ampera, followed by a Tesla Model S 85 in 2014 – I’ve been driving fully electric ever since. In 2015, I also took part in the WAVE Trophy. Combustion engines must be replaced by electric motors, because only then can the switch in electricity supply to CO₂-free energy sources also automatically make transport CO₂-emission-free. Otherwise, the car will first have to wait for synthetic fuels, and that takes too long.

The break: a visit to Amprion’s Brauweiler system control and Hambach open lignite mine.

It came as it had to come: after arguing time and again with the “evil nuclear energy lobby” of Nuklearia on Facebook, I received an invitation from a work colleague to visit the Amprion network control room in Brauweiler in October 2018, even with a lecture and guided tour by the head of system management, Joachim Vanzetta, current Chair of the Board of ENTSO-E. I was delighted to receive first-hand confirmation that we are on the right track with the energy transition and 100% renewables.

The day before, I still visited the lignite misery at the Hambach open pit mine along with the dwindling Hambach Forest – fossil energy sources are and remain the real problem – that was always clear to me. The lecture on the day itself was sober and very informative. We learned a lot about buying electricity and managing a power grid, and that working on a power grid has nothing to do with balanced energy quantities. The system management only works with all kinds of software support with 15-minute updated forecasts for renewable energies, which, as we know, have priority in the power grid and according to whose supply all power plants must – and so far still can – flexibly adjust.

Hardly any wind, no sun

The foggy day itself was rather sobering for renewables: hardly any wind and no sun. We were even allowed to visit the main switchboard, where otherwise only experts and high-ranking politicians are granted exclusive access. The engineers had their hands full keeping the lignite and nuclear power plants at full load and buying power on the market. The large red-green-yellow laser display on the main switchboard in front of us showed Amprion’s entire network with the power values currently being run. Almost always, something has to be readjusted.

Source: Amprion GmbH/@livrozet.photography

With these impressions in my luggage, I went home again – to argue with the ‘Nuclearians’ on the net about the energy turnaround – or so I thought.

Rethinking – the Ecomodernist Manifesto

The visit had done more to me than I first thought. What serves demand of electricity at any given time when renewables are not delivering? The power must be kept available – how does that work? Permanently and surely only with power plants that can follow the demand.

But everything has to be CO2-free, that’s the only way it makes sense. It was the time when I had to think anew about an energy turnaround with “100% renewable”.

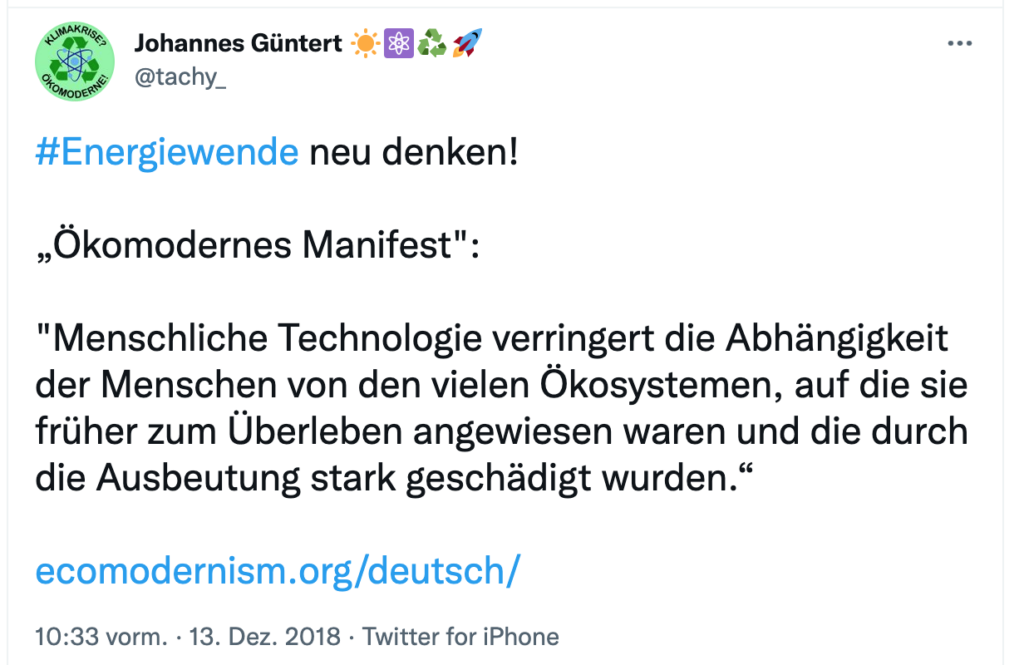

In connection with this, I unfortunately don’t remember exactly how it came about, how I found the Ecomodernist Manifesto and took a closer look at it – because two months after the visit to Brauweiler, I then tweeted about it for the first time:

The ecomodern approach says: we must avoid our harmful impact on nature, even though we produce and consume energy, use raw materials, practice agriculture and live a life of prosperity. This impressed me a lot as a concept, because I have never been able to do anything with “DeGrowth” (practicing radical renunciation and avoiding economic growth), but have always preferred technical solutions to the problem of climate change. And now I also knew why I felt so uncomfortable at the one anti-nuclear demonstration against Fessenheim in 2011 after Fukushima. Because it is instinctively not my style to demonstrate so naively against technology.

Therefore, I started to question nuclear energy anew as well, to inform myself about the current state of affairs (for example, I shared this article about the new generation of nuclear power plants in the “Süddeutsche Zeitung” on Facebook already on Dec. 4, 2018) and had some insights as a result. From now on I started to make my peace with nuclear power and also with Nuklearia. Nuclear energy itself is not the end in itself in ecomodernism, but only a means to an end. I, at least, got answers to my questions about “nuclear waste”, safety and costs….

Therefore, I started to question nuclear energy anew as well, to inform myself about the current state of affairs (for example, I shared this article about the new generation of nuclear power plants in the “Süddeutsche Zeitung” on Facebook already on Dec. 4, 2018) and had some insights as a result. From now on I started to make my peace with nuclear power and also with Nuklearia. Nuclear energy itself is not the end in itself in ecomodernism, but only a means to an end. I, at least, got answers to my questions about “nuclear waste”, safety and costs….

For me, ecomodern energy means nuclear energy plus renewables, but without the fossil backup and storage madness.

But these questions are meant to be the start of many more posts on this blog explaining the how and why of an eco-modern approach to the climate crisis and environmental protection.